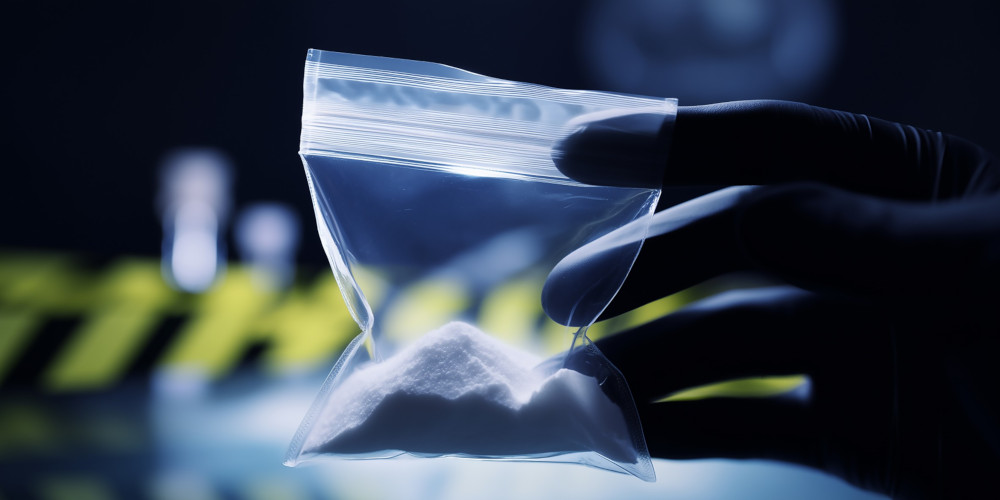

When people talk about addiction, they almost always focus on the substance. Meth. Cocaine. Heroin. Pills. Weed. Alcohol. They talk about the drug as if it exists in a vacuum, as if addiction is simply chemical dependency, personal weakness, or brain chemistry gone wrong. But anyone who has watched addiction unfold in real life knows the truth: the drug itself is often only half the problem. The other half is the environment around it.

Addiction is a social disease. It spreads through friendship circles, party groups, WhatsApp chats, after-work drinks, weekend rituals, shared secrets, shared chaos, shared habits. And at the centre of this ecosystem sits a person most people don’t want to talk about, the dealer. Not the stereotypical hardened criminal selling in alleyways. The new dealer is a friend, a co-worker, a club acquaintance, a “good vibe” guy, a connector, a facilitator, a gatekeeper of fun.

People don’t become addicted to substances alone. They become addicted to the world that the substance belongs to. And in that world, the dealer holds the gravitational pull.

This article explores how social circles create addiction, how the “drug dealer effect” shapes behaviour, and why so many people relapse not because of cravings, but because they can’t escape the people who made using feel normal.

Not the Villain You Expect

Most people imagine drug dealers as dangerous criminals who operate in the shadows. But in reality, the typical modern dealer is someone socially connected, charismatic, friendly, trustworthy, or at least perceived that way. They blend into parties, festivals, gyms, bars, office circles, and friend groups. They are rarely strangers. Usually, they’re the person who “always knows someone,” the person who can “sort you out,” the person people gravitate toward when they want to take the night up a level.

This familiarity is what makes the drug dealer effect so powerful. Purchasing drugs doesn’t feel like a criminal transaction. It feels like part of the friendship. It feels normal. It feels safe. It feels like just another part of the social dynamic. The dealer becomes someone everyone trusts, not because they are trustworthy, but because they are convenient. They are the key to the ritual.

This is how addiction becomes woven into social life. The dealer isn’t a dangerous outsider. They’re part of the group. And when the group depends on them, the substance becomes embedded in the identity of the circle.

The Social Gravity That Pulls People In

Addiction rarely begins because someone wakes up wanting to destroy their life. It begins with the group. It begins with a weekend, a party, a friend’s encouragement, a moment of curiosity. It begins with people wanting to feel included, wanted, connected. The drug becomes secondary. The real addiction is belonging.

The dealer effect thrives on this psychological vulnerability. People gravitate toward the person who makes them feel included in the fun. It’s human nature to want to fit in, especially in groups that seem confident, exciting, and socially rewarding. The social reinforcement is intoxicating long before the substance is.

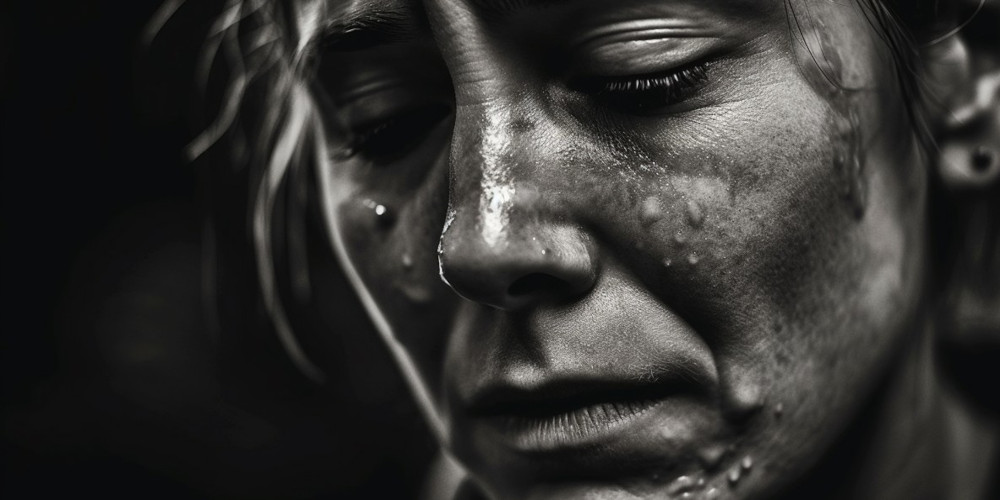

People don’t keep using because they love the drug. They keep using because they love the feeling of being part of something, a group, a vibe, a moment, an energy. And once that group has become associated with the drug, removing the drug feels like removing the friendship itself. This is why early recovery feels so lonely for many people. They aren’t just giving up the substance. They’re giving up the world built around it.

The Dealer as the Unofficial Leader

Every social circle has roles. The joker. The planner. The caretaker. The risk-taker. The dependable one. And then there’s the dealer, the unofficial leader. The dealer sets the pace, the intensity, the frequency, the rituals. They decide when things start. They control when the group escalates from drinking to using. They decide what substances appear and when. Their presence shapes the entire atmosphere.

People don’t realise how reliant the group becomes on that leadership. They wait for cues. They follow the energy. They mirror the behaviour of the person who controls access to the drug. This creates a subtle hierarchy where the dealer holds power, not through force, but through social influence.

Many people end up deep in addiction simply because the leader of their circle normalised the behaviour. If the dealer uses heavily, the group mimics it. If the dealer mixes substances, the group experiments with mixtures. If the dealer uses midweek, the group loses its boundaries too. The real addiction is to the dynamic, not the drug.

The Emotional Bond That Feels Like Loyalty

One of the most overlooked elements of addiction is the emotional connection people build with their dealer. The dealer becomes a source of comfort, familiarity, and reliability. They are someone the user turns to in moments of stress, loneliness, celebration, or insecurity.

The user begins associating the dealer with relief.

With escape.

With feeling understood.

With being part of something.

This emotional bond is incredibly dangerous because it feels like friendship, but it is based on convenience and dependency. The dealer provides what the person wants in the moment, not what they need long-term. But because that provision feels good, the user mistakes it for care. This is why people feel guilty when they stop contacting a dealer. It feels like abandoning a friend. But the relationship was never equal. It was built on an exchange, and the user always pays the higher price.

The Dealer as the Biggest Trigger in Recovery

One of the strongest predictors of relapse is not cravings, trauma, or withdrawal. It’s contact with old using friends, especially the person who used to supply the drugs. The dealer represents the entire world of addiction. One message, one visit, one casual conversation can crack open the doorway to relapse.

People underestimate this trigger because they think they can handle a simple conversation. They think they can control themselves. They think they can be polite without falling back into patterns. But addiction isn’t just chemical. It’s behavioural conditioning. The brain remembers the dealer as the starting point of the ritual. Even hearing their voice can activate old cravings.

This is why recovery requires distance, real distance, not polite distance. But distance is difficult when the dealer is also a friend, a colleague, or someone socially embedded in the person’s life. People don’t relapse because they’re weak. They relapse because they kept stepping into the gravitational pull of the same orbit.

Why Leaving the Group Feels Like Losing a Family

People often underestimate the emotional devastation of giving up their using circle. It’s not simply letting go of bad influences. It’s letting go of some of the only people who felt like home during the addiction phase. Using groups often share intense moments, secrets, nights out, emotional conversations, chaotic experiences. These moments create the illusion of closeness. People mistake shared destruction for deep connection. They believe the group understands them better than anyone else because the group saw them at their most unfiltered, intoxicated, vulnerable moments.

But that closeness is chemically manufactured. It does not survive sobriety. It collapses the moment the substance is removed from the dynamic. Recovery feels brutally lonely because people suddenly realise that the friendships they thought were meaningful were only meaningful in the presence of the drug.

The Dealer Doesn’t Change

One of the hardest moments in recovery is realising that you’ve outgrown the world your dealer thrives in. You’re trying to build a new life, develop new habits, stabilise your brain, reconnect with yourself, and the dealer is still stuck in the same loop. They don’t want you to change because your sobriety threatens their social ecosystem.

Some dealers pressure people to come back.

Some guilt-trip them.

Some minimise their recovery.

Some make jokes.

Some send “checking in” messages that are really invitations.

Some pretend to care in order to maintain access.

The dealer is not interested in your recovery.

They’re interested in keeping the circle alive, because the circle keeps their lifestyle alive.

This is why cutting ties is essential.

You cannot recover in the environment that made you sick.

Families Don’t See the Dealer

Families often ask why their loved one keeps going back to the same people. They don’t understand the bond, the attachment, the unspoken loyalty. They don’t understand why someone would risk their life for a group of friends who consistently lead them into destructive behaviour.

But the family is only seeing the consequences. They aren’t seeing the environment where the addiction feels like comfort. They aren’t seeing the validation, the belonging, the emotional numbness, the freedom from judgment. They aren’t seeing how the group makes the substance feel normal, even necessary.

To the user, leaving the circle feels like losing a piece of themselves.

To the family, staying in the circle feels like losing them entirely.

Both experiences are real.

But only one leads to healing.

Recovery Means Rebuilding Your Social World From Scratch

Healing from addiction isn’t just about detoxification. It’s not just therapy, or introspection, or willpower. It’s social reconstruction. People in recovery must build a new world, new routines, new friendships, new environments, new ways of coping, new forms of belonging. It’s not easy. It’s not quick. It’s not comfortable. But it is necessary.

The dealer effect fades the moment the person forms new bonds, bonds built on authenticity rather than intoxication, bonds where connection doesn’t depend on chemicals or chaos. Recovery requires replacing the entire social ecosystem, not just removing the substance.

The person you love is not choosing drugs over you.

They are choosing the world where drugs live, because that world feels familiar.

Help them build a new one.